advertisement

Importance of outflow facility

Richard F. Brubaker

Clinicians are aware of the importance of reducing intraocular pressure for the treatment of glaucoma. Evidence continues to mount that this method of attack, both in high tension glaucoma and to a lesser extent in normal tension glaucoma, reduces the rate of ganglion cell loss that characterizes the disease.

Fortunately for their patients, there is an increasing number of effective ocular hypotensive agents that are available to clinicians for lowering intraocular pressure. Some of these drugs lower pressure by suppressing aqueous flow, and others lower pressure by increasing outflow. If drugs are equally effective at lowering steady state intraocular pressure, does how they work make any difference?

To answer this question, we must consider whether the steady state condition - when inflow and outflow are exactly equal - typifies the normal state of affairs. If it does, we need not worry about mechanism of action. But if there are frequent disturbances to the steady state during the common activities of daily living, we must look more carefully.

Consider a single example of these activities - drinking water. After drinking water or any hypotonic fluid, there is absorption of water into blood and body tissues including the eye. There is an increase of volume of the eye and a consequent rise of intraocular pressure.

How quickly the eye recovers from a transient rise of intraocular pressure depends exclusively on the pressure sensitivity of aqueous humor outflow. The classical term for this parameter is 'facility of outflow'. Poor facility of outflow accounts for the elevated pressure in glaucoma. Low facility of outflow in glaucoma also accounts for the instability of intraocular pressure and the larger circadian rhythm that is commonly observed in this disease.

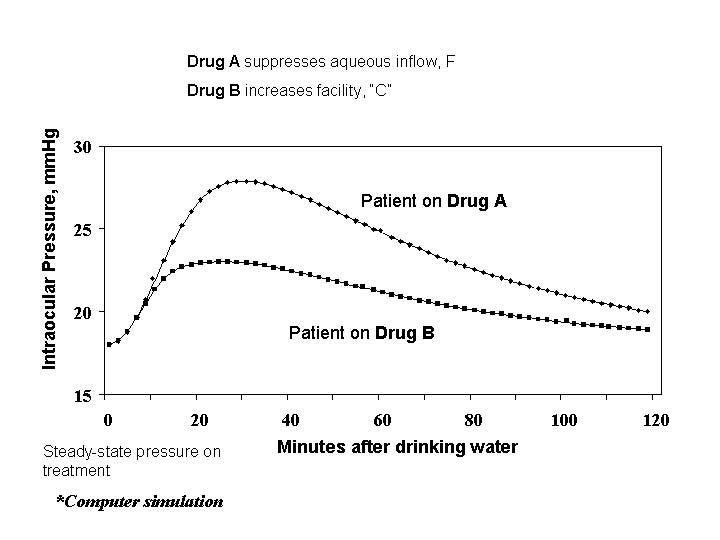

Computer simulation of a hypothetical case of glaucoma can be helpful in answering our original question about the importance of drug mechanism. Imagine a patient whose untreated steady state intraocular pressure is 28 mmHg. Imagine also that each of two drugs, Drug A and Drug B, is capable of reducing the pressure of this hypothetical patient to 18 mmHg. Drug A acts by suppressing the formation of aqueous humor. Drug B acts by improving the facility of outflow.

The figure depicts a computer simulation of the rise and fall of intraocular pressure in the eye after the patient ingests a liter of water. On Drug A, the aqueous suppressor, the pressure rises higher and for longer than on Drug B, the facility of outflow enhancer. The computer simulation shows how drugs that have the same effect on steady state intraocular pressure can have different effects on the speed of recovery from pressure perturbations.

Facility of outflow gives natural stability to intraocular pressure. Ocular hypotensive drugs for the treatment of glaucoma that improve it are preferable, other things being equal, to drugs that do not. Although tonography may not be a diagnostic tool, it can give some insight into the risks of patients' daily routines.